Books Printed Befor 1950 on North American Native Art

I is for Ignoble: Stereotyping Native Americans

By Arlene Hirschfelder and Paulette F. Molin

Published February 22, 2018

A common conventionalities in the contemporary U.s., oftentimes unspoken and unconscious, implies that anybody has a right to use Indians as they see fit; everyone owns them. Indianness is a national heritage; it is a fount for commercial enterprise; it is a costume one can put on for a party, a youth activity, or a sporting issue. This sense of entitlement, this expression of white privilege, has a long history, manifesting itself in national narratives, popular entertainments, marketing schemes, sporting worlds, and self-improvement regimes. [ane]

From the earliest menstruation of European colonization, images of Indians found expression in early drawings, engravings, portraiture, political prints, maps and cartouches, tobacconist figures, weather vanes, coins and medals, and books and prints. Initially, depictions of Native males and females were used to symbolize the Northward American continent in the international iconography of the solar day, representations that proliferated. The Indian Queen, an allegorical figure in use past the cease of the sixteenth century, symbolized the Western Hemisphere. Her successor, the Indian Princess, became representative of the American colonies. During the Revolutionary flow, America was portrayed every bit a feathered Indian defying British tyranny in printed materials of the mean solar day.

As the United States grew, it developed a mythology that helped provide Americans with a laudable national heritage while serving to rationalize the dispossession and conquest of ethnic peoples. As National Museum of the American Indian curator Cécile R. Ganteaume points out, "American Indian imagery has been used by the federal government to distinguish the Us from other nations and to define the nation for its citizens, past U.S. military to express military machine might, by American corporations to signify integrity and past designers . . . to add together luster and cachet to commercial products." [two]

Institutionalized throughout the nation and exported to other countries, these images and others include dual portrayals of the good Indian (those who help Europeans) and the bad Indian (those who resist Europeans), nostalgic vanishing, brave warriors, romantic princesses, and countless ignoble images of brutality and deposition. Such representations obliterate or mask the realities of tribal nations struggling to maintain their populations, lands, resource, and sovereignty.

Questions about ethnic people often begin with terminology. "At the museums and on social media," Kevin Gover, managing director of the National Museum of the American Indian, comments, "people inquire at least once per 24-hour interval when we are going to take 'American Indian' out of our name." [3] As he responds, "Native Americans use a range of words to describe themselves, and all are appropriate. Some people refer to themselves as Native or Indian; most prefer to exist known by their tribal affiliation . . . if the context doesn't demand a more encompassing clarification." [4] With respect to Canada, Gover notes that "terms such as First Nations and Showtime Peoples are preferred." [5]

American Indians are richly diverse, yet all too oftentimes their public portrayals—in books, advertisements, store signs, terminology, and even children'southward toys and games—are greatly at odds with actual Native peoples and cultures. As the National Congress of American Indians points out, "There are 567 federally recognized Indian Nations (variously called tribes, nations, bands, pueblos, communities and native villages) in the United States. Approximately 229 of these ethnically, culturally and linguistically diverse nations are located in Alaska; the other federally recognized tribes are located in 35 other states." [6] In addition, there are state recognized tribes across the country equally well as other differences.

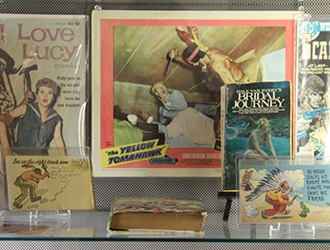

This essay explores selected themes centered on centuries-erstwhile stereotypes of American Indians: "Tomahawks and Knives": Stereotypical Violence; "Words Are Weapons": Language Representations; "Stereotypes Sell": Commercialization of Indians; "Self-Shaping": Playing Indian; "Braves" and "Chiefs": Indian Mascots; and "I is for Indian": World of Children. It is illustrated with images from the Jim Crow Museum, drawn from its drove of objects depicting Native Americans and consistent with its goal to tell stories of injustice towards all groups.

"Tomahawks and Knives": Stereotypical Violence

"Tomahawks and Knives": Stereotypical Violence

Almost whatsoever portrait that we come across of an Indian, he is represented with tomahawk and scalping knife in hand, as if they possessed no other but a savage nature. Christian nations might with equal justice be always represented with cannon and brawl, swords and pistols. [7]

Throughout U. S. history, Euro-Americans committed countless acts of violence against Native people. Such acts include extermination or genocide, theft of Indian lands and resources, captivity and enslavement, forced removals from homelands, and schooling aimed at destroying Native cultures.

Violence continues today. A report by the U.S. Department of Justice shows that "American Indian and Alaska Native women and men suffer violence at alarmingly high rates." [8]

In an American Psychiatric Clan blog mail, research scientist Melanie Peterson-Hickey observes that loftier suicide rates amidst Native Americans are well documented, noting that the "trauma resulting from a history of race-based policy, bigotry and oppression has significant and longstanding impact." [ix]

Nonetheless, equally Tuscarora Main Elias Johnson has pointed out, American Indians are represented as savage, with tomahawk and scalping knife in manus. In dissimilarity, Euro-Americans are depicted as innocent victims of savagery, especially from Indian males.

It is believed that European representations of Native people as violent date back to as early every bit 1591, when engraver Theodor DeBry engraved and published artist Jacques LeMoyne'due south 1564-65 drawing of Indian scalping. Furthermore, from the 17th to the nineteenth centuries, non-Indian observers portrayed Indians intent on "savage state of war" more violent than "civilized" combat of European and American governments. Increasingly lurid details of Indian savagery also appeared in captivity narratives, published from the 1600s to the 1800s, accounts of non-Indians captured and held prisoner by Indians. Dime novels, inexpensive booklets starting time marketed in 1859, became popular as well. This bestselling fiction portrayed Indians as savages preying on defenseless Euro-Americans.

Wild Westward shows, performed across North America and Europe from the belatedly 1800s into the 20th century, dramatized Indian attacks on stagecoaches and cabins besides as mock battles between cavalry and Indians. William "Buffalo Bill" Cody and other showmen, including Plains Indians, drew huge audiences. These shows, and related influences, inspired filmmakers to produce Westerns depicting hordes of Indians attacking Euro-Americans. Every bit a matter of fact, many American Indians were taken captive by non-Indians, tortured, incarcerated, murdered, and expelled into slavery. Because Europeans and Euro-Americans colonists threatened Native peoples, many resisted mightily to defend their families and homelands.

The ongoing perception of Indians as unsafe contributes to negative expectations, interactions, and consequences. Thus, Indians are incarcerated at high rates, encounter discrimination and hate crimes, and feel other negative impacts. Stereotyped Indian violence also leads non-Indians to fear Native people.

Nevertheless, the "brutal nature" representation of Indians, voiced by Elias Johnson, continues to pervade American civilisation via school curricula, books and toys, sports teams, media advertisements, and other means. Such representations prevent others from seeing Native people realistically, including in a range of roles, settings, and occupations.

"Words Are Weapons": Language Representations

"Words Are Weapons": Language Representations

In contrast to the inane stereotype of the Indian as soundless, we know from the vast storehouse of our oral traditions that Aboriginal peoples were peoples of words. Many words. Amazing words. Cultivated words. They were neither wordless nor illiterate in the context of their linguistic and cultural roots. [10]

Although more than 300 Native languages existed in what is at present the continental United States, "equally different from each other as Turkish, English, and Chinese," that number greatly diminished in the aftermath of European colonization. [xi] Ethnic population loss through disease and war exacted a cost as did ongoing measures to Europeanize and Christianize Native people at the expense of their own cultures and languages. Such measures included the institution of mission and government boarding schools to implement English language-only and other harsh policies. As federal commissioners wrote, "their barbarous dialect should be blotted out and the English language substituted." [12]

With English, a lexicon of words and phrases became entrenched, a shorthand manner to refer to all Native people, language reflecting stereotypical attitudes and behaviors. Savage, pagan, injun, brave, cadet, chief, redskin, squaw, papoose, and other terms became commonplace. The negative impact was heightened with the addition of adjectives such equally wild, dingy, pesky, sneaky, and worse. "In an abusive society," activist Suzan Shown Harjo points out, "language is a control machinery . . . and words are weapons used to bespeak condition information, such equally who are the junior and superior folks." [13]

"Words such as savage, buck, squaw, and papoose," author Mary Gloyne Byler emphasizes, "practise not bring to heed the same images every bit exercise the words man, male child, adult female and babe." [fourteen] While some words (squaw, papoose) tin can exist traced to specific Native languages, they accept been removed from their cultural origins and turned into generic, pejorative labels. Other terms may have been benign, but have been weaponized over time, also past context. Fifty-fifty Pocahontas, the proper noun of a historical figure, is misused every bit a slur.

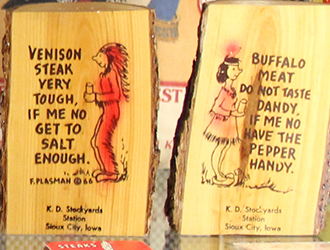

Compounding slurs, media such every bit Hollywood films and Wild West shows contributed to the notion that American Indians, regardless of linguistic background, speak a fictional, substandard version of English. Variously described as Hollywood or Pidgin English or "Tonto-speak," its grammatical markers include formulaic grammar, including the apply of "um" ("speak-um") and "me" instead of "I" ("me speak-um"). This language became entrenched, endlessly repeated across time and place. It portrays Indians every bit silent and wordless or incapable of speaking proper English or other "civilized" languages.

"Stereotypes Sell": Commercialization of Indians

"Stereotypes Sell": Commercialization of Indians

Stereotypes sell. To this day, consumers recognize the stylized Indian chief on cans of Calumet baking powder and the kneeling Indian maiden on packages of State O'Lakes butter. [15]

For hundreds of years, merchants have used images of American Indians to annunciate and market merchandise. Products include tobacco, associated with Native Americans, advertised via tobacconist figures, or cigar store Indians, and more than. According to author Ralph Sessions, "English tobacconists were among the first to capitalize upon the image of the Native Americans." [16] Figures, intended to represent the inhabitants of the New Globe, advertised shops carrying the "Indian weed." "The earliest visual evidence of the use of a tobacconist figure in America," Sessions notes, appears outside a tobacco shop depicted in an 1810 watercolor by painter Baroness Hyde de Neuville. [17]

The tobacconist figures, made from forest or cast atomic number 26, soon became popular across Due north America. At beginning, "the female figure . . . was by far the more pop, outnumbering male figures four to 1." [18] Omnipresent as today'southward neon signs and billboards, these figures normally appear as generically "Indian." Cigar store Indians and other products associated with tobacco continue to appear across commercial venues.

Marketers also invoked Native associations with herbs and plants to sell medicinal concoctions. Pop during the 1800s, Indian medicine shows, a number featuring Indian or Indian-impersonator performers, pitched a range of patent or proprietary (across the counter) nostrums or remedies as cure-alls, among them Kickapoo Indian Salvage, Big Chief Liniment, and Indian Stomach Bitters. The burgeoning advertizement industry was patently instrumental to the rising of medicine shows during the menstruum. As author Brooks McNamara points out, "Nostrum advertisement continued to develop on a prodigious scale in nineteenth-century America," with presses pouring along "a sea of handbills, posters, flyers, free magazines, trade cards" and more to promote products. [xix]

Native nutrient associations, besides, contributed to companies promoting a range of products using Indian names, titles, and images. "Ad objectifies," author Deborah Doxtator notes. "Information technology transforms the image of historical figures such equally Tecumseh … and Pontiac into piddling objects that can exist possessed, used up and thrown away." [20] The same is true of commercialization that exploits titles (Large Chief Meat Snacks) and "loanwords" (Squaw Peas). Furthermore, when companies advisable tribal names like Sioux (Sioux Bee Honey/Sue Bee Honey), they propose an association with specific Indian nations.

One time advertisers in America, Nippon, and other countries began using images of Native people after the 1850s, historian Daniel Francis writes: "Of a sudden images of the Indian were appearing on the pages of mass-circulation magazines, on billboards, on the shelves at the local supermarket." [21] These images relegate people to a timeless past. "Any appropriation of American Indian images or cultural imagery to sell a product," scholar Victoria E. Sanchez asserts, "amounts to perpetuation of institutionalized racism and is a contributing cistron to insensitive stereotypes, prejudice, discrimination, and stigmatization." [22]

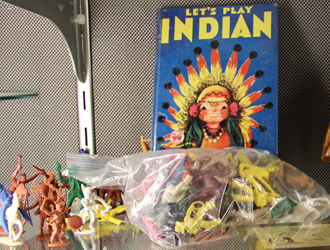

"Self-Shaping": Playing Indian

"Self-Shaping": Playing Indian

While minstrel shows have long been criticized as racist, American children are still socialized into playing Indian. Columbus Day celebrations, Halloween costumes and Thanksgiving reenactments stereotype Indigenous Peoples equally one big distorted culture. We are relegated to racist stereotypes and cultural caricatures. [23]

Allow's Play Indian, a children's book by Madye Lee Chastain, is one of countless examples of playing Indian, a practice engaged in past outsiders who appropriate, or take on, American Indian identities and cultural means. Chastain'south main character transforms herself into "a really truly dressed-up painted Indian," who runs, whoops, and waves her tomahawk. [24] As columnist Ruth Hopkins notes, "Some folks contend that since it's adequate to clothes upwards as a cowboy, they should get a pass for dressing upwardly equally an 'Indian.' Wrong." [25] While children frequently clothes up to play a cowboy, nurse, or fire fighter, these are occupations. Being American Indian is not a profession or vocation. It is a human identity, tribally specific and integral to Native personhood and nationhood.

Let's Play Indian is not an isolated example of playing Indian. Really, the practice has a long history. Equally scholar Rayna Light-green writes: "Nigh from their very arrival in the Americas, Europeans found information technology useful, perhaps essential, to 'play Indian' in America, to demand that tribal peoples 'play Indian,' and to export the performances dorsum to Europe, where they thrive to date." [26] The Boston Tea Political party, which helped spark the American Revolution in 1773, is an early example. Sounding war whoops and masquerading as Mohawks, colonial men boarded ships in Boston Harbor and threw chests of tea overboard to protest British tea taxes. White males such as these were the kickoff of many participants to engage in Indian play. Woodcraft Indians, Camp Fire Girls, Boy Scouts, Wild West and Indian medicine shows, hobbyists, and sports teams are amidst numerous examples. Playing Indian cuts across race, course, gender, historic period, and grouping affiliations. Some people engage in such "play" temporarily, as in Halloween costuming, just others appropriate Indian names and identities on an ongoing basis.

Playing Indian likewise extends to depictions of animals dressed as Indians in a variety of products, including books and toys. These portrayals are dehumanizing, suggesting that Native people are creatures of fantasy and non fully human.

Playing Indian with one-size-fits-all images of American Indians is contrary to actual Native peoples, past or present. Such practices foreclose other people from learning nigh, or understanding, Native America. Such "play" masks low per-capita incomes, high unemployment, poor health, and other realities. As Philip J. Deloria, author of Playing Indian, points out: "…the means in which white Americans have used Indianness in creative cocky-shaping accept continued to be pried apart from questions about inequality, the uneven workings of power, and the social settings in which Indians and non-Indians might really meet." [27]

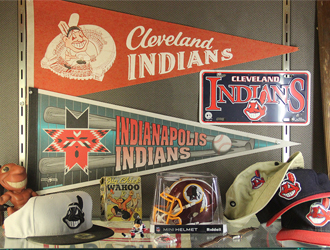

"Braves" and "Chiefs": Indian Mascots

"Braves" and "Chiefs": Indian Mascots

Native American mascots have very footling to do with Native Americans. They practise non, nay, cannot, represent indigenous men and women. Much like blackface, such inventions and imaginings, meant to represent a racial other, tell usa much more than about Euro-Americans….They reverberate and reinforce the fundamental features of racial and gendered privilege in a settler society, particularly a sense of entitlement to take and remake without consent and to do so without the burden of history, the challenges of knowing, or the risk of penalty. [28]

A pop version of playing Indian arose in the early on office of the twentieth century in organized sports, with team names such as Braves, Chiefs, Indians, Savages, Redskins, and Warriors. These monikers, evoking masculine ethics of bravery and aggression, became widespread at a range of institutions, including K-12 schools, colleges and universities, and amateur and professional person able-bodied leagues and franchises.

Teams with "Indian" names come with a diverseness of practices, amid them the adoption of "ruby-face" mascots costumed every bit Plains Indians, ersatz Indian dances and rituals at halftime, face paint and feathered headdresses, and the antics of war whooping, tomahawk chopping fans. Ring members, drill teams and cheerleaders (including "Indian princesses," "Redskinettes," and the like) contribute to the overall theme. Such representations have become normalized, a familiar role of everyday America. "These images are and then powerful," activist Charlene Teters has testified, "that many non-native people do not see usa every bit modernistic people with a valued history, living culture, language or a future." [29] Challenging such images requires seeing them for what they are (and are not). Author Dave Zirin, for instance, notes: "I started looking into [the Redskins] more after a young girl of Native American beginnings saw the logo on a media folder in my handbag and asked me fearfully why 'the human'southward head had been chopped off.'" He concluded: "…in one case you run into information technology, you tin can't unsee it." [30]

Team logos, rife with "chopped off" Indian heads, are emblazoned on fields and arenas, programs and memorabilia, and across a range of venues. Audiences, fans or non, are bombarded with radio, television, paper, and electronic media coverage. Teams, especially franchises worth billions of dollars, market an astonishing array of commercial products, such as pennants, caps, mugs, plates, notebooks, mascot figures, bobble heads, and even toilet paper. Starting with infant apparel and other merchandise, marketing is aimed at all age groups, the better to groom fans and continue acquirement flowing into squad coffers.

Demeaning "Indian" linguistic communication, too, reinforces imagery, equally in:

Hail to the Redskins.

Hail Victory!

Braves on the warpath.

Fight for erstwhile D.C.

Scalp 'um, swamp 'um, we volition

Take 'um large score. [31]

Although some teams have denied or sanitized racist versions of fight songs and other representations, the historical tape reveals the truth. Through efforts past opponents of Indian mascots, a number of institutions, especially at the K-12 and college levels, have changed a range of practices, including team names. Professional teams such as the Redskins and the Cleveland Indians have been the about resistant to change.

"I is for Indian": Globe of Children

"I is for Indian": Globe of Children

But I am injure and often outraged by how my children feel their Indianness in mainstream America. [32]

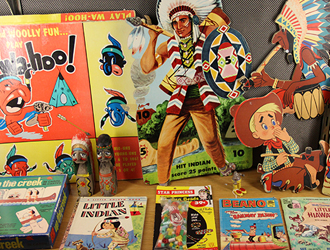

The lives of children are saturated with American Indian stereotypes: "I for Indian" in alphabet books, "Ten Little Indians" song and dance, plastic "Indian villages," coffee-can "tom-toms," cardboard totem poles, "Indian" Barbie dolls, Pocahontas costumes, and more. As educator Jim E. Warne has testified, "Today's average U.S. education about Indians is reduced to cutting out construction paper feathers, coloring book tepees and tomahawks, and Pilgrim hats for Thanksgiving." [33]

Consistent with such instruction, "I for Indian" too often appears in alphabet blocks, cards, and books. Juxtaposed with objects (A for apple, B for ball), it is likewise accompanied by a dancing, whooping, war painted "Indian" and other stereotypical imagery. Besides objectifying Native peoples, "I for Indian" is known to manifest "the anachronistic placement of past-tensed 'Indians' with modern items or settings."[ 34] Such anachronisms contribute to misconceptions about Native Americans, past or nowadays.

Native people are also treated as objects in counting songs, books, and toys. "Ten Petty Indians" is the best known instance past far, appearing in nursery schoolhouse curricula, toys, recordings, games, YouTube videos, and theater productions. Written in 1868 as "Ten Little Injuns" by songwriter Septimus Winner, this hitting "comic vocal and chorus" features "injuns" dying past dissimilar means "until there were none." [ 35] Adults continue to teach the vocal, seemingly oblivious to its violent, racist history, counting downwards Indians to annihilation.

Clinical psychologists report that constant encounters with false images result in Native children internalizing stereotypes that interfere with their developing positive self-images and racial identities. Likewise, researchers have studied the development of racial awareness, attitudes, and feelings in young children. "The first 6 years of life are important for the evolution of all social attitudes," psychologist Gordon Allport has written. "A bigoted personality may be well nether mode by the historic period of six…." [36] For writer Mary Gloyne Payne Byler, "far from being harmless, stereotypes are one of the most common manifestations of prejudice and i of the most persistent." [37]

Whatever the source, inaccurate images and information about Native people are especially harmful during children'due south formative years. In a study past Children At present, a child advocacy organisation examining children's perceptions of race and class in the media, Native youngsters said they see themselves as "poor," "drunkard," "living on reservations," and "an invisible race." [38] The Children NOW study concludes that "Native American youth are concerned about portrayals of their race in the media." [39] So are countless historians and other educators who object to the maltreatment of Native peoples and cultures. Scholar Michael Dorris puts information technology bluntly: "To deprive our children (who grow up to get no less deprived adults) access to the wealth and sophistication of traditional Native American societies is indefensible . . . this treasure trove of experience and intelligence, perfected over tens of thousands of years residence on this continent, is allowed to be eclipsed past impaired, racist drivel." [40]

References

1 C. Richard King, redskins: Insult and Make (Lincoln: Academy of Nebraska Press, 2016), 100.

ii Cécile R. Ganteaume, "Americans: Major New Exhibition Asks, Why Do Images of American Indians Permeate American Life?" National Museum of the American Indian magazine, vol. 18, no. 3 (Fall 2017): 20-27.

3 Kevin Gover, "Five Myths about American Indians," The Washington Post, November 22, 2017. https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/five-myths/five-myths-about-american-indians/2017/11/21/41081cb6-ce4f-11e7-a1a3-0d1e45a6de3d_story.html?utm_term=.c73ca14f9617 (accessed January 13, 2018).

4 Gover, "Five Myths near American Indians."

5 Gover, "Five Myths about American Indians."

half-dozen National Congress of American Indians, "Tribal Nations and the United States: An Introduction," January 15, 2015. http://world wide web.ncai.org/about-tribes (accessed January xiii, 2018).

7 Elias Johnson, A Native Tuscarora Chief. Legends, Traditions and Laws of the Iroquois, or Half-dozen Nations, and History of the Tuscarora Indians. Lockport, NY: Union Publishing Co., 1881. [reprints available]

8 André B. Rosay, "Violence Against American Indian and Alaska Native Women and Men," U.Due south. Department of Justice, Role of Justice Programs National Found of Justice, May 2016. https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/249736.pdf (accessed Jan fifteen, 2018).

9 Melanie Peterson-Hickey, "American Indians, Mental Wellness, and the Influence of History," American Psychiatric Association blog mail service, Nov 6, 2015. https://www.psychiatry.org/news-room/apa-blogs/apa-blog/2015/11/american-indians-mental-health-and-the-influence-of-history (accessed January 15, 2018).

10 Emma LaRocque, "Hither Are Our Voices—Who Will Hear?" Preface to Writing the Circumvolve: Native Women of Western Canada, compiled and edited by Jeanne Perreault and Sylvia Vance (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1993), xv.

xi Elizabeth Seay, Searching for Lost City: On the Trail of America'south Native Languages (Guilford, CT: The Lyons Press, 2003), ix.

12 J.D.C. Atkins, "The English Language in Indian Schools," in Americanizing the American Indians: Writings past the "Friends of the Indian" 1880-1900, ed. Francis Paul Prucha (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Printing, 1978): 197-206.

13 Suzan Shown Harjo, "Scout Your Language!" Indian State Today, July 4, 2001. https://indiancountrymedianetwork.com/news/picket-your-language/ (accessed October 26, 2017).

14Mary Gloyne Byler, "Taking Some other Look," in Through Indian Eyes: The Native Experience in Books for Children, eds. Beverly Slapin and Doris Seale (Philadelphia, PA: New Society Publishers, 1992): 81-87.

xv Jeffrey Steele, "Reduced to Images: American Indians in Nineteenth Century Advertising," in Dressing in Feathers: The Construction of the Indian in American Popular Culture, ed. Southward. Elizabeth Bird (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1996): 45-64.

16 Ralph Sessions, The Shipcarvers' Art: Figureheads and Cigar-Shop Indians in Nineteenth-Century America (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton Academy Press, 2005), 86.

17 Sessions, The Shipcarvers' Art, 86.

xviii "Cigar-Shop Indian," in Encyclopedia of N American Indians, ed. Frederick Hoxie (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1986), 123.

19Brooks McNamara, Step Correct Up: An Illustrated History of the American Medicine Show (Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Co., 1976), 13, sixteen.

20Deborah Doxtator, Fluffs and Feathers: An Exhibit on the Symbols of Indianness: A Resource Guide (Brantford, Ontario: Woodland Cultural Centre, revised edition, 1992), 46.

21Daniel Francis, The Imaginary Indian: The Image of the Indian in Canadian Civilisation (Vancouver, B.C.: Arsenal Lurid Press, 1993), 175.

22Victoria East. Sanchez, "Buying into Racism: American Indian Product Icons in the American Marketplace," in American Indians and the Mass Media, eds. Meta K. Carstarphen and John P. Sanchez (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2012): 153-168.

23Dwanna Fifty. Robertson, "Playing 'Indian' and Color-Blind Racism," Indian Country Today, September 20, 2013. https://indiancountrymedianetwork.com/news/opinions/playing-indian-and-color-bullheaded-racism/ (accessed Oct 30, 2017).

24Madye Lee Chastain, Let's Play Indian (New York: Wonder Books, 1950).

25Ruth Hopkins, "My Native Identity Isn't Your Plaything. Finish with the Mascots and 'Pocahotties,'" The Guardian, June xix, 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/jun/xix/my-native-identity-isnt-your-plaything-mascots-pocahotties (accessed October ii, 2017).

26Rayna Dark-green, "The Tribe Called Wannabee: Playing Indian in America and Europe." Sociology, vol. 99, no. 1 (1988): xxx-55.

27Philip J. Deloria, Playing Indian (New Haven, CT: Yale Academy Press, 1998), 189-190.

28C. Richard Male monarch, redskins: Insult and Brand, 31-32.

29Charlene Teters, in "Stolen Identities: The Bear upon of Racist Stereotypes on Ethnic People," Hearing before the Committee on Indian Affairs, United States Senate, 112th Congress, May 5, 2011. https://world wide web.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CHRG-112shrg66994/pdf/CHRG-112shrg66994.pdf ( accessed Oct 29, 2017).

30Dave Zirin, "You Tin't Unsee It: Washington Football Name and Quiet Acts of Resistance," The Nation, September 5, 2014. https://world wide web.thenation.com/article/archive/y'all-cant-unsee-it-redskins-and-quiet-acts-resistance/(accessed Oct 6, 2017).

31Connie Griffith, My Life with the Redskins (New York: A.S. Barnes & Co., 1947), 39.

32Nancy Marie Mithlo, "Our Indian Princess": Subverting the Stereotype (Santa Fe, NM: School for Avant-garde Enquiry, 2009), viii.

33Jim Eastward. Warne, in "Stolen Identities: The Bear upon of Racist Stereotypes on Indigenous People." https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/CHRG-112shrg66994/pdf/CHRG-112shrg66994.pdf (accessed October 29, 2017).

34Robert B. Moore and Arlene Hirschfelder, "Feathers, Tomahawks and Tipis: A Study of Stereotyped 'Indian' Imagery in Children's Motion-picture show Books," in American Indian Stereotypes in the World of Children: A Reader and Bibliography, 2nd ed., eds. Arlene Hirschfelder, Paulette Fairbanks Molin, and Yvonne Wakim (Lanham, Physician: The Scarecrow Press, 1999): 55-lxxx.

35Julianne Jennings, "The History of 'Ten Little Indians,'" Indian Country Today, Oct 11, 2012. https://indiancountrymedianetwork.com/civilization/social-issues/the-history-of-10-little-indians/ (accessed January 15, 2018).

36Gordon Allport, The Nature of Prejudice (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co., 1954), 297. [Reprint edition: New York: Bones Books, 1979]

37Mary Gloyne Payne, "Editorial: Mary Gloyne Payne," Indian Affairs, no. 62 (December 1965), 5.

38Children NOW. A Different Globe: Native American Children's Perceptions of Race and Class in the Media. (Oakland, CA: Children NOW, 1999), https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED436234.pdf (accessed January 15, 2018).

39Children Now.

twoscoreMichael A. Dorris, "Foreword to the First Edition," in American Indian Stereotypes in the Globe of Children: A Reader and Bibliography, twond ed., seven-eight.

mashburntheyinecaut.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.ferris.edu/HTMLS/news/jimcrow/native/homepage.htm

0 Response to "Books Printed Befor 1950 on North American Native Art"

Post a Comment